At a gathering in the Holbrook-Palmer Park Pavilion in Atherton last month, as a resident began to speak about the incessant and loud airplane noise blanketing his neighborhood, 150 other attendees from Atherton, Menlo Park, Portola Valley and Palo Alto suddenly looked skyward.

As if on cue, a large aircraft rumbled overhead.

“I can’t hear you,” the resident quipped.

The crowd applauded approvingly, but residents say that airplane noise over their neighborhoods is no laughing matter.

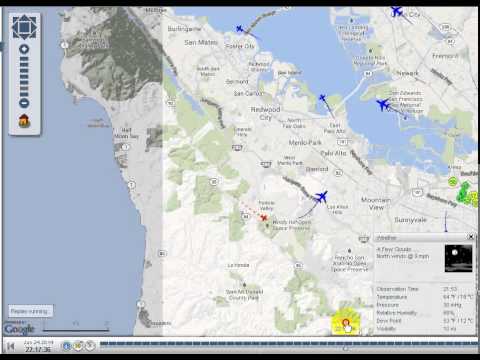

In the 14 years since U.S. Rep. Anna Eshoo and then-Palo Alto Mayor Gary Fazzino secured an agreement with San Francisco International Airport (SFO) to reduce plane noise by 41 %, the 70 daily flights over Palo Alto have ballooned to as many as 200, according to charts on online flight-track maps.

Residents say the skies are turning into an aeronautic superhighway over Midpeninsula cities and that federal levels for acceptable noise, which date to the 1970s, are obsolete and need to be updated — pronto.

Compounding the issue, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is currently rolling out a plan in the Bay Area to make the airspace more efficient — a plan that residents say is making the noise problem earsplittingly worse. Called Next Generation Air Transportation System, or NextGen, the plan switches air-traffic control from a ground-based system to a satellite-based one, which the FAA claims will allow it to guide and track planes more precisely and facilitate an expected growth in air traffic.

As part of NextGen, commercial jetliners fly within a narrower band of airspace than before. They also descend using a continuous decrease in altitude rather than following a stepped descent, as previously done — but that increases noise as engines throttle for the decline, residents say.

The NextGen changes have alarmed communities across the nation where the program has rolled out.

Starting in June 2012 over Queens, New York, planes began flying at low altitudes every 20 seconds to a minute from 6 a.m. to midnight, said Janet MacEneaney, president of Queens Quiet Skies. MacEneaney lives about 10 miles away from LaGuardia Airport.

“For the past 2.5 years, we’ve had an egregious amount of noise,” she said.

Now, from Palo Alto to Brisbane, the issue is heating up. More than 900 Woodside, Portola Valley and Ladera residents signed a petition and letter to the FAA regarding the noise. Four Portola Valley and Woodside residents filed a petition with the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit on Sept. 26 challenging the FAA’s finding that its plans for optimizing future use of the Bay Area’s airspace won’t have any significant impact.

What’s more, residents say, the fledgling Surf Air commuter line of propeller planes, which uses San Carlos Airport, is adding a layer of smaller, allegedly noisier commercial aircraft over neighborhood rooftops.

Citizens’ groups are springing up along the Midpeninsula with the support of their city governments: Sky Posse Palo Alto; CalmTheSkies in Atherton and Menlo Park; and the Ad Hoc Citizens Committee on Airplane Noise Abatement for the South Bay in Portola Valley and Woodside.

The City of Palo Alto has sought to become a member of the SFO Community Roundtable — which addresses airport noise issues and represents every major city in San Mateo County [ see map – San Mateo County is just south of San Francisco] — but has been denied membership because it’s outside the county. But Palo Alto Mayor Nancy Shepherd and City Manager James Keene have both weighed in on NextGen’s environmental-impact study, Shepherd said.

Palo Alto residents who are looking into the issue are seeking to form alliances with the established groups.

Stewart Carl, a member of Sky Posse Palo Alto, began noticing the flight and noise changes around the fall of 2013. From his third-story Palo Alto home office, he has heard the thunderous noise as he’s worked late into the night and early morning.

“I’ve lived there for 18 years and it never bothered me. Now I’m hearing jet noise constantly. I started wondering, ‘What is going on?'” he said.

Residents last week gathered in a Palo Alto office conference room to discuss strategies and share information. They considered an email from an SFO official in the Noise Abatement Office regarding changes in flight paths. He stated that there have been no changes in 2014, but a change did occur in 2013.

Prior to July 2013, arrivals were split between routes over land and over San Francisco Bay. But the FAA permanently directed international planes to fly over the Midpeninsula after the Asiana Airlines crash, when the pilot landed short of the runway, he noted.

The FAA has declined to comment on matters related to the SFO flights because of the pending litigation by the Portola Valley and Woodside residents. But numbers tell part of the story.

This year, 68 percent of flights have come overland from the south compared to 54 percent in 2010, according to SFO data.

For Palo Alto, 48 percent of flights came over land in 2014 compared to 45 percent in 2010.

Palo Alto residents believe the flight paths have shifted to the south. SFO spokesman Doug Yakel said that flight patterns may expand or contract based on increases or decreases in air traffic volume, but he did not specify how far or where the contractions and expansions have occurred.

Tina Nguyen, one of the plaintiffs challenging the FAA’s finding of no significant impacts in its environmental review, said tracking the flights through the online airport Web Tracker confirms flights are coming in further south than before.

In addition, Southwest and Virgin America increased their traffic into SFO in 2007. The airport has compensated for it by sending many flights into a holding pattern over Woodside and Portola Valley, while they hold their place in the queue, she said. She verified the traffic patterns by studying the online SFO and San Jose flight trackers. All of these flights also pass over Palo Alto, she said.

Yakel confirmed that traffic around the three Bay Area airports is up about 2 percent compared to last year, mainly due to increases at SFO and San Jose. In August, SFO recorded 18,664 arrivals, he said. Of these, 7,470, or 40 percent, flew over Palo Alto at an altitude of 10,000 feet and lower.

Decibel levels and how they are measured are a major point of contention between the FAA, residents and congressional members.

When Eshoo and Fazzino made their agreement with SFO, the altitude for planes flying over the border of Menlo Park and Palo Alto was to be 5,000 feet rather than 4,000, according to a May 12, 2000, letter she wrote to members of UPROAR, a local airplane-noise group.

Eshoo wrote that the change was anticipated to reduce noise by one to two decibels at ground level.

SFO also agreed to install a permanent noise monitor at the Palo Alto and Menlo Park border to aid enforcement. But Bert Ganoung, SFO’s manager of aircraft noise abatement, said the decibel monitor was never installed.

When 9/11 and fears of SARS led to a drop in the number of people who were flying, airport revenues decreased, he said. The decreased number of flights also resulted in a lesser need to monitor noise levels, he added.

In 2002, a letter from the head of the noise office withdrew the offer of a decibel monitor. Cities were offered monitors if they paid for them, with SFO agreeing to do annual maintenance, but most no longer saw a need, he said.

An Eshoo spokesperson said the permanent decibel monitor was awaiting final permitting when 9/11 dried up air traffic and the funding for the site.

“At this time, cities can pursue a portable decibel monitor program at no cost,” the spokesperson said in an email. “The State of California accepts this quarterly monitoring system as an acceptable substitute to permanent noise monitors under Title 21 — California Noise Standards. Again, it is incumbent upon cities to pursue this option, and they are encouraged to do so.”

Nguyen’s group hired its own aviation-noise expert, who conducted tests and found that between Aug. 26, 2013, and Sept. 11, 2013, 61 arrival flights had a peak noise level of 80 decibels near Skyline Boulevard in Woodside, she said.

The noise seems to stem from low-flying planes that are violating agreements SFO made in 1998 and 2000 to keep flights above Skyline above 8,000 feet and at the Palo Alto and Menlo Park border at 5,000 feet, Nguyen said. Data from the SFO Noise Abatement Office shows that more than 80 percent of arrival flights on a typical Sunday violated the 8,000-foot agreement, Nguyen said.

Data obtained from the FAA also showed that between Jan. 1 and May 31, 2013, 60.4 percent of flights arriving from the west were below 8,000 feet over Woodside — with more than half of those flying below 6,000 feet.

But Ganoung countered that planes fly at those altitudes only when weather is good.

The FAA has a 65-decibel Day-Night Average Sound Level standard, which has been in place since 1976 and is considered compatible with residential neighborhoods. But the standard is “outdated and disconnected from the real impact that air traffic noise is having on our constituents and should be lowered to a more reasonable standard of 55 decibel DNL,” wrote 26 members of the U.S. House of Representatives, including Eshoo and Rep. Jackie Speier, in a Sept. 12 letter to the FAA.

The letter demanded an update of national sound-level standards and that the agency expedite a five-year noise-level study the FAA has underway.

Most European countries have dropped the standard to 55 decibels, Carl pointed out.

Nguyen said the FAA’s use of the day-night average is exactly that — an average. It doesn’t note flights that exceed 65 decibels nor remove the night curfews when planes are not flying.

A better weighted analysis would be to study noise levels from single airplanes passing over homes, the residents contend. The U.S. First District Court of Appeal supported that contention in an opinion on an Aug. 30, 2001, lawsuit filed by the group Berkeley Keep Jets Over the Bay Committee against the Port of Oakland. In that case, the Port’s Board of Commissioners had approved a plan to reconfigure and expand the Oakland International Airport to accommodate nearly double the number of flights between 1994 and 2010. The board had concluded there would not be significant noise and emissions problems based on the 65-decibel level, which is an average over a 24-hour period. But the environmental-impact study did not account for the disturbance of increased nighttime flights. The plaintiffs argued that the Port’s reliance on the average provided a skewed representation of noise issues.

The three-judge panel agreed.

“This conclusion is derived without any meaningful analysis of existing ambient noise levels, the number of additional nighttime flights that will occur … the frequency of those flights, to what degree single overflights will increase noise levels over and above the existing ambient noise level at a given location, and the community reaction to aircraft noise,” the judges wrote.

The members of Congress raised similar concerns in their letter to the FAA.

“It is imperative that the FAA properly balance emission and noise concerns. This includes variations of daily flight routes, continuous descent approaches and rapid ascents,” they wrote regarding the NextGen program.

Air-traffic volume

NextGen has been touted by the FAA as a necessary and long-overdue program that will modernize the nation’s air-traffic operations systems and prepare for a future of increased sky traffic. The FAA’s Aerospace Forecast projects that commercial air-traffic volume will nearly double over the next 20 years. SFO forecasts a 2 percent annual increase in air traffic, Yakel said.

“The airport can accommodate this rate without any adding runway capacity until about 2025-2030. At that point, airlines would have to start using larger aircraft, and/or the airport would have to expand runway capacity,” Yakel said.

“To deal with the projected increases,” Carl said, “the NextGen program will channel air traffic into a handful of narrow flight paths starting up to 200 miles from an airport and will allow air-traffic control to use much tighter aircraft-to-aircraft spacing.

“The net effect is all of the air-traffic and noise that was spread out over a large area is concentrated over a smaller population living under the handful of precision flight paths into an airport,” he said.

Prior to NextGen, pilots charted their own course until 20 miles from the airport. This approach allowed for flight paths that were more spread out, and with them, the noise. Under NextGen, the flight paths will go directly on over particular neighborhoods, he said.

The plan is to have five paths into SFO. Three of the five come over Palo Alto, and the city is getting roughly half of the arrival traffic, Carl added.

Aircraft spacing, which is now about 6 miles between planes, will reduce to 1 mile or less, he said. [??]

Higher noise levels over Palo Alto are projected under the FAA’s plan, according to consultants ATAC Corporation. The greatest increase by 2019 is expected to be between 1 and 2.7 decibels in the Esther Clark Park neighborhood, west of Foothill Expressway. Residents under the flight path over Esther Clark, Green Acres, Barron Park, then heading north along Jordan Middle School, Walter Hays Elementary School and Eleanor Pardee Park are expected to experience an estimated 1.2-decibel increase, with an average of 45.9 decibels in noise, according to the report.

Palo Alto locations surveyed ranged between receiving 32 and 45.6 decibels of sound, with most falling in the 43- to 44-decibel range.

But overall, the environmental study concluded that NextGen would have no significant impacts on noise. Using radar data to examine routes to SFO, Oakland Metropolitan International Airport, Norman Y. Mineta San Jose International Airport and Sacramento International Airport, ATAC Corporation’s analysis found that the program would not result in a 1.5 decibel or higher increase in areas already at or above 65 decibels and would not result in 3-decibel increases or higher in areas now exposed to noise between 60 and 65 decibels. The air-traffic changes would also not result in increases of 5 decibels or higher in areas exposed to noise between 45 and 60 decibels, according to the report.

But residents pointed out that the study once again is based on the standard of average decibel levels and doesn’t consider the noisiest flights. To alter that standard, however, change must happen at the federal level, said John Shordike, the attorney who represented the Berkeley group in the Oakland case.

“Unless there is new legal authority on the federal level under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), (the FAA) can continue to use this ridiculous and meaningless average,” he said.

The FAA Modernization Act of 2012, which authorized $63.4 billion for the FAA modernization, including $11 billion for NextGen, alters National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) review for any NextGen procedures, MacEneaney of Queens said.

Her organization is currently working to change that provision when the act comes before Congress for renewal in 2015, she said.

What will the FAA do with the newly opened territory outside the narrow jetliner routes created by NextGen?

The act requires the FAA to provide airspace to military, private and commercial drones by Sept. 30, 2015.

[Details – see FAA https://www.faa.gov/uas/legislative_programs/section_333/ ]

The FAA has been hard pressed to find such space for these small, unmanned aircraft amid cargo planes, business jets and commercial airliners. But funneling jetliners into precise, pinpoint-accurate traffic lanes would free up the surrounding space. Currently, drones are restricted to small airspaces away from airports and at low altitudes away from cities.

.

.

.

.

.

.