Bill Hemmings: An ICAO deal that falls well short of “carbon-neutral growth” target will have no credibility

Date added: 7 July, 2016

Bill Hemmings, (from T&E) explains the hurdles to ICAO agreeing an environmentally meaningful deal in October. The global aviation sector needs to play its part in the international aspiration, from the Paris Agreement, to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees C, or 2 degrees at worst. However, ICAO is not looking as if this is likely, largely due to the differences between historical and current CO2 emissions, and current and future growth rates, between airlines from countries (US and Europe largely) with historic aviation sectors, and those of developing countries, with young aviation industries. Ways to apportion the CO2 fairly need to be agreed, but solutions favour one group or the other. The developing countries (including Brazil, South Africa, and Nigeria) want their aviation CO2 to be exempted from any scheme. But emissions gap would amount to around 40-50% of the total, and so directly threatens the integrity of the commitment to carbon neutral growth from 2020, to which IATA pays lip service. Then there is the problem how to determine what percentage of emissions above the 2020 baseline airlines should have to offset each year. European and US airline CO2 is barely growing, but the CO2 from some is rising by 8% per year. US airlines do not want to pay for this. The issues are complicated. Read Bill’s explanation.

.

An ICAO deal that falls well short of carbon-neutral growth target will have no credibility

Thursday 7 July 2016 (GreenAir online)

By Bill Hemmings (Aviation Director of sustainable transport group Transport & Environment)

ICAO’s triennial Assembly, to agree on how to address the climate impact of international aviation, is just two months away. (Starts 27th September, ends 7th October). States undertook in 2013 to develop a global measure that would cap annual aviation CO2 at 2020 levels.

Largely reflecting industry concerns over cost, it was later agreed that this would be achieved by requiring airlines to purchase carbon offsets for all emissions above the 2020 baseline.

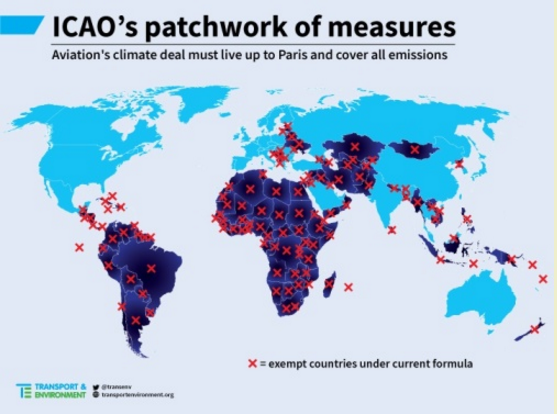

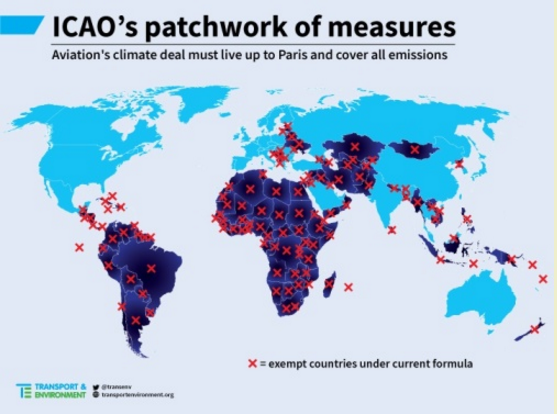

Industry and the US argued strongly that a global deal was preferable to a so-called patchwork of measures, a reference to Europe’s first-of-its-kind emissions trading system (ETS).

The EU was prevailed upon to drastically reduce the scope of the ETS to give ICAO and its parties time to sort out details of the global market-based measure (GMBM) before the forthcoming assembly. Regrettably, important details remain unresolved, potentially putting any credible and environmentally meaningful ICAO agreement at risk.

At the heart of the issue is the question of differentiation, a fundamental aspect of all international climate agreements. In the case of ICAO, differentiation means asking how the obligations of all carriers can reflect the fact that the vast bulk of historical emissions are due to legacy carriers headquartered chiefly in North America and Europe. Should developing country carriers have to share an equal burden? A Chinese proposal to have obligations related to the share of carriers’ emissions since 1990, when developing country aviation was largely in its infancy, was rejected on grounds that there was no data.

Initially, Europe, and later civil society, called for a route-based system where carriers on routes between geographic regions might bear varying carbon obligations depending on the density of traffic or country status – a rough indicator of where historical emissions lie.

In the end, however, the ICAO Council President opted for a simple system for determining eligibility and obligations based on traffic generated by each country’s registered carriers, together with a GDP per capita formula that was later discarded.

Most African countries, which account for barely 2-3% of global emissions, were always going to be exempt. But the President’s proposal exempted a second tier of countries with a larger share of emissions – including Brazil, South Africa, Nigeria and possibly even smaller EU countries.

The emissions gap due to these exemptions is now some 40-50% and directly threatens the integrity of the commitment to carbon neutral growth from 2020. The position of countries like China and Russia in any agreement also remains unclear.

The only element of differentiation left in the deal – apart from the huge exemptions gap – is the formula for determining what percentage of emissions above the 2020 baseline carriers should have to offset each year.

The ICAO proposal has all carriers together offsetting the average growth of the sector above 2020 levels. This introduces an important element of differentiation, as fast-growing carriers – more often than not from the emerging markets – will have to offset a lower percentage of their emissions above 2020 levels than if the obligation were to be based on individual carrier growth.

However, US carriers represented by A4A together with IATA are arguing for an approach based more on individual airline growth. And now it seems the US supports this position, calling for carriers over time to pay a percentage closer to their actual growth rate.

The reason is not hard to find; according to the latest IEA statistics, US international outbound CO2 emissions between 2010 and 2013 declined on average 0.02% a year while Chinese international outbound emissions grew on average 8.02% a year in the same period.

If we assume national airline traffic/emissions growth is pretty closely related to growth in a country’s total outbound emissions, then we can roughly estimate a carrier’s annual growth in emissions. So if the US and Chinese trends above are any indication of the state of the industry post 2020, under the individual approach a carrier like United Airlines might well incur zero or near zero offset costs while an airline like China Southern might have to pay over 8%.

The table below (see http://www.greenaironline.com/news.php?viewStory=2257 ) from the most recent IEA data suggests airlines from Mexico, India, Brazil, Argentina and Nigeria might be in a similar position if the formula for determining offsetting obligations was based on individual carrier growth.

Such a formula would represent a pretty good deal for US carriers like United. The more so given that unlike Europe where domestic emissions are covered by its ETS, US carriers are currently bound by no domestic climate measures, yet they generate within the US alone almost 20% of all aviation CO2 globally.

On top off this, at its recent AGM, IATA has stated bluntly that “emissions which are not covered by the scheme, as the result of phased implementation or exemptions, should not be re-distributed to those operators which are subject to the scheme.”

Since it is only airlines that will have to offset their emissions, it is either the case that negotiations in the next few weeks prevail upon a wider group of countries to join the GMBM and their routes close the gap, or carriers on routes within the GMBM offset more in order to close the gap. The ideal solution is a mixture of minimising the gap through increased participation and then closing the gap through a higher offsetting obligation on carriers operating on developed country routes. Industry should be to the fore in calling for such an outcome.

However, rather than use its influence to help resolve this, IATA’s statement regrettably seems tantamount to industry washing its hands of the huge emissions gap problem. It removes any possibility of achieving carbon neutral growth from 2020, something industry claimed to support.

Even worse, suggestions are now circulating that there should be no eligibility criteria for exemptions; states should be given the option at the Assembly of stating whether they would like their airlines to opt in or not. A patchwork of measures indeed.

Industry and the US need to think again. A deal which falls well short of the target of carbon neutral growth from 2020 goal will have no credibility.

As it is, such a commitment is a very modest first step for the sector to deliver the level of reductions that the Paris agreement requires and would need to be strengthened and supplemented quickly.

And if there is no deal, or a weak deal – possibly because the US, industry and others wind back on differentiation – then we are back to where we started, perhaps choosing between patchworks, but after three wasted years while the planet warms.

Bill Hemmings is Aviation Director of sustainable transport group Transport & Environment

http://www.greenaironline.com/news.php?viewStory=2257

.

.

.

The Paris Agreement and the ICAO process to adopt effective climate measures are not separate. The Paris Agreement covers all anthropogenic emissions, sets out important principles on carbon markets, and sends a clear signal that the aviation sector must act.

Download the full document “THE PARIS AGREEMENT AND IMPLICATIONS FOR REDUCING AVIATION EMISSIONS” here.

This states that the Paris Agreement:

“SETS A LONG-TERM GOAL FOR ALL MAN-MADE EMISSIONS

The Agreement commits parties to limit an increase in global temperatures to well below 2°C, pursue eforts to limit that increase to 1.5°C, and reduce emissions to net zero. This would achieve a balance between anthropogenic emissions by sources and removals by sinks of greenhouse gases since the second half of the 20th century. Not only would this transpire on the basis of equity, but in the context of sustainable development and eforts to eradicate poverty. As aviation emissions, both international and domestic, are very much caused by humans, this directly brings them into the ambition and requirements of the Agreement.

.

It “ESTABLISHES THE PRINCIPLE OF INCREASING AMBITION OVER TIME

The contributions put forward by parties to date are insufficient to achieve the 1.5/well below 2°C objectives. The Agreement therefore requires the ambition of these contributions to rise over time in order to reach the 1.5/well below 2°C objectives. These increases in ambition will take place as part of a regular, five-year review process starting with a stock-take in 2018. Simply maintaining the United Nations International Civil Aviation Organization’s (ICAO) Global Market Based Measure (GMBM) target of stabilizing net emissions at 2020 levels will be inconsistent with the 1.5/well below 2°C objective. It is important that the ICAO commits to substantially increasing its ambition to bring its reduction targets in line with temperature objectives as soon as possible.”

.

The document concludes:

“THE PARIS AGREEMENT AND THE ICAO MBM (Market Based Measure) ARE MUTUALLY SUPPORTIVE

The Paris Agreement and the ICAO process to adopt efective climate measures are not separate. The Paris Agreement covers all anthropogenic emissions, sets out important principles on carbon markets, and sends a clear signal that the aviation sector must act. While measures adopted at the ICAO level must have unique features – such as respecting the principle of nondiscrimination between airline operators – this is not a barrier to swift and effective action to reduce aviation’s climate impact. The spotlight is now on ICAO to live up to its commitment to finalize a (global market based measure) GMBM at its upcoming Assembly in October 2016.”

http://icsa-aviation.org/the-paris-agreement-and-implications-for-reducing-aviation-emissions/

Posted: Thursday, July 7th, 2016. Filed in Climate Change News, Recent News.