Major airlines say they’re acting on climate change – research reveals how little they’ve achieved

Date added: 18 February, 2020

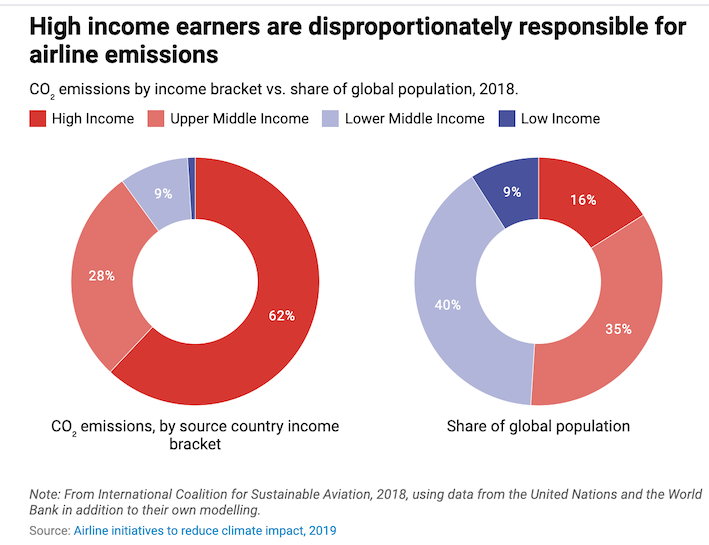

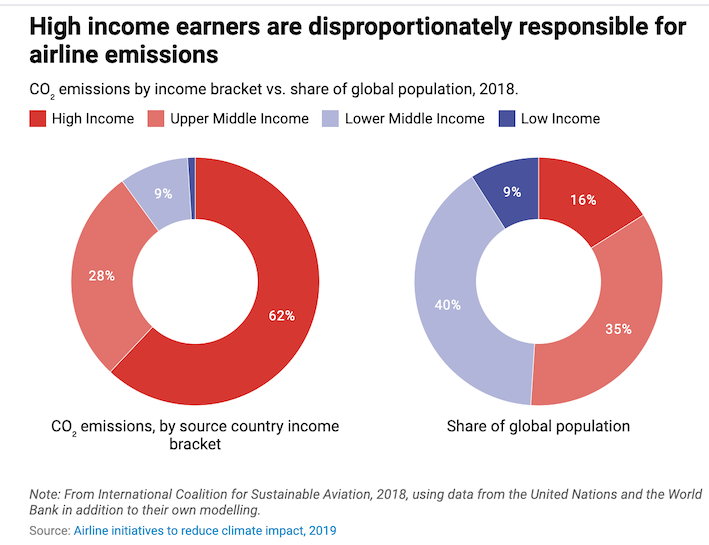

Research by Griffith University, New Zealand, has shown that the climate claims of most airlines are pretty thin. Several airlines have announced plans to become “carbon neutral”, or trial new aviation fuels. But looking at the world’s 58 largest airlines, when what is being done is compared to the continued growth in emissions, it is nowhere near enough. There have been improvements in the amount of carbon per seat kilometre – the “carbon efficiency.” But that is eclipsed by growth in number of flights and passengers. The study found the improved efficiency (fleet renewal, engine efficiency, weight reductions and flight path optimisation) amounted to a 1% cut in emissions, while the industry aims to cut by 1.5%. That was totally outweighed by annual growth of 5.2% in the carbon emitted by the industry globally. Industry figures show global airlines produced 733 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions in 2014. Falling fares and more people wanting to fly saw airline emissions rise 23% in just five years, 2014 -19. Higher-income travellers from around the world have had disproportionately large aviation CO2 emissions; they form a total of 16% of global population, but 62% of global aviation CO2. People need to cut the amount they fly …

.

Major airlines say they’re acting on climate change. Our research reveals how little they’ve achieved

February 16, 2020

By Susanne Becken

Professor of Sustainable Tourism and Director, Griffith Institute for Tourism, Griffith University

Disclosure statement

Susanne Becken is on the Sustainability Advisory Panel of Air New Zealand. Her report, Airline initiatives to reduce climate impact, was co-written with Paresh Pant. This research paper was done in partnership with travel technology company Amadeus.

Partners: Griffith University. Griffith University provides funding as a member of The Conversation AU. The Conversation UK receives funding from these organisations

If you’re a traveller who cares about reducing your carbon footprint, are some airlines better to fly with than others?

Several of the world’s major airlines have announced plans to become “carbon neutral”, while others are trialling new aviation fuels. But are any of their climate initiatives making much difference?

Those were the questions we set out to answer a year ago, by analysing what the world’s largest 58 airlines – which fly 70% of the total available seat-kilometres – are doing to live up to their promises to cut their climate impact.

The good news? Some airlines are taking positive steps. The bad news? When you compare what’s being done against the continued growth in emissions, even the best airlines are not doing anywhere near enough.

More efficient flights still drive up emissions

Our research found three-quarters of the world’s biggest airlines showed improvements in carbon efficiency – measured as carbon dioxide per available seat. But that’s not the same as cutting emissions overall.

One good example was the Spanish flag carrier Iberia, which reduced emissions per seat by about 6% in 2017, but increased absolute emissions by 7%.

For 2018, compared with 2017, the collective impact of all the climate measures being undertaken by the 58 biggest airlines amounted to an improvement of 1%. This falls short of the industry’s goal of achieving a 1.5% increase in efficiency. And the improvements were more than wiped out by the industry’s overall 5.2% annual increase in emissions.

This challenge is even clearer when you look slightly further back. Industry figures show global airlines produced 733 million tonnes of CO₂ emissions in 2014. Falling fares and more people around wanting to fly saw airline emissions rise 23% in just five years.

What are the airlines doing?

Airlines reported climate initiatives across 22 areas, with the most common involving fleet renewal, engine efficiency, weight reductions and flight path optimisation. Examples in our paper include:

- Singapore Airlines modified the Trent 900 engines on their A380 aircraft, saving 26,326 tonnes of CO₂ (equivalent to 0.24% of the airline’s annual emissions);

- KLM’s efforts to reduce weight on board led to a CO₂ reduction of 13,500 tonnes (0.05% of KLM’s emissions).

- Etihad reports savings of 17,000 tonnes of CO₂ due to flight plan improvements (0.16% of its emissions).

Nineteen of the 58 large airlines I examined invest in alternative fuels. But the scale of their research and development programs, and use of alternative fuels, remains tiny.

As an example, for Earth Day 2018 Air Canada announced a 160-tonne emissions saving from blending 230,000 litres of “biojet” fuel into 22 domestic flights. How much fuel was that? Not even enough to fill the more than 300,000-litre capacity of just one A380 plane.

Carbon neutral promises

Some airlines, including Qantas, are aiming to be carbon neutral by 2050. While that won’t be easy, Qantas is at least starting with better climate reporting; it’s one of only eight airlines addressing its carbon risk through the systematic Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures process.

About half of the major airlines engage in carbon offsetting, but only 13 provide information on measurable impacts. Theses include Air New Zealand, with its FlyNeutral program to help restore native forest in New Zealand.

That lack of detail means the integrity of many offset schemes is questionable. And even if properly managed, offsets still avoid the fact that we can’t make deep carbon cuts if we keep flying at current rates.

What airlines and governments need to do

Our research shows major airlines’ climate efforts are achieving nowhere near enough. To decrease aviation emissions, three major changes are urgently needed.

All airlines need to implement all measures across the 22 categories covered in our report to reap any possible gain in efficiency.

Far more research is needed to develop alternative aviation fuels that genuinely cut emissions. Given what we’ve seen so far, these are unlikely to be biofuels. E-fuels – liquid fuels derived from carbon dioxide and hydrogen – may provide such a solution, but there are challenges ahead, including high costs.

Governments can – and some European countries do – impose carbon taxes and then invest into lower carbon alternatives. They can also provide incentives to develop new fuels and alternative infrastructure, such as rail or electric planes for shorter trips.

How you can make a difference

Our research paper was released late last year, at a World Travel and Tourism Council event linked to the Madrid climate summit. Activist Greta Thunberg famously sailed around the world to be there, rather than flying.

Higher-income travellers from around the world have had a disproportionately large impact in driving up aviation emissions.

This means that all of us who are privileged enough to fly, for work or pleasure, have a role to play too, by:

- reducing our flying (completely, or flying less)

- carbon offsetting

- for essential trips, only flying with airlines doing more to cut emissions.

To really make an impact, far more of us need to do all three.

https://theconversation.com/major-airlines-say-theyre-acting-on-climate-change-our-research-reveals-how-little-theyve-achieved-127800

.

Despite flying being the single fastest way to grow our individual carbon footprint, people still want to fly. Passenger numbers even grew by 3.3% globally last year alone. The hype around “Flygskam” – a global movement championed by climate activist Greta Thunberg that encourages people to stop travelling by plane – seems to have attracted more media attention than actual followers.

A 2019 survey found that although people in the UK were increasingly concerned about aviation emissions – they were also more reluctant to fly less. This might reflect how flying has become normalised in society, aided by ticket prices which are on average 61% cheaper in real terms than in 1998. I’m increasingly asked by peers about how they can fly “sustainably”, the “greenest” airlines, or the “best” carbon offsets to buy. People want to avoid flight shame, without avoiding flights.

The industry has reacted quickly. Websites like Skyscanner, used to compare flight options between destinations, now show customers a “greener choice” – displaying how much less C02 a certain flight emits, compared to the average for that route. These green choices are determined to be flights that use more direct routes, airlines that have newer aircraft, or can carry more passengers.

While there are cases where two airlines operating the same route can produce very different emissions, on short-haul routes, emissions differences are invariably small – usually less than 10%. The greenest option would be to travel by train, which has as much as 90% fewer emissions than equivalent flights. However, Skyscanner stopped showing passengers train options in 2019.

Meanwhile, popular budget airline Ryanair – whose CEO only recently admitted climate change isn’t a hoax – now claims to have the greenest fleet of air planes in Europe. The company’s modern, fuel efficient planes – alongside its ability to fill them with passengers – does make it the “greenest” air travel option out there. However, Ryanair had a total of 450 planes in operation in 2019 (compared to only 250 in 2010) – meaning that despite its fuel-efficient planes, the sheer quantity of fuel they burn is why they were named one of Europe’s top ten polluting companies in 2019.

Last year also saw carbon offset schemes become popular. These schemes allow passengers to pay extra so their airline can invest in environmental projects on their behalf – thereby making a flight theoretically “carbon-neutral”. British Airways now offsets all of its customers’ domestic UK flights, while Ryanair also has a scheme allowing passengers to buy offsets for their flights, with proceeds going to projects including a whale protection scheme – which appears completely unconnected to reducing carbon at all.

Easyjet has also started buying offsets on behalf of all its passengers – costing a total of £25 million a year. This has apparently been a successful PR move, with internal research finding that passengers who were aware of the offsetting policy were more satisfied with their flight than customers who didn’t know.

Passengers might feel satisfied, but whether their offsets actually reduce carbon is less clear. Critics question the time-lag associated with offsets, especially tree-planting schemes. A plane that flies today pollutes today – but a tree planted today won’t remove carbon for years. As for “avoided deforestation” projects, which aim to protect existing trees, proving these trees wouldn’t have survived without offset funding is almost impossible.

Read more: Exaggerating how much CO₂ can be absorbed by tree planting risks deterring crucial climate action

Airlines often claim that their offsets save high levels of carbon, at a conveniently low price. For example, Easyjet only invests £3 per tonne of carbon it emits in a carbon offset scheme. But such a low-ball investment might not even be able to give these carbon offset schemes the finances needed to actually offset the effects of one tonne of carbon. For context, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme currently trades carbon at £21 a tonne, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change thinks carbon should be traded at a minimum of £105 a tonne. Newer, and more expensive offset models – which extract carbon directly from the air look promising – but are hard to scale up.

The other danger of these cheap offsets is that travellers might believe they solve the problems caused by flying – so they won’t change their travel behaviour. Indeed, one government minister even argues that there’s no need for people to fly less, because low-carbon and electric flights are around the corner. Despite reports that solar or battery-powered planes are coming to the rescue, current plane technology is going nowhere fast.

This is partly because jet fuel on international flights isn’t taxed, which leaves little financial incentive for the industry to invest in big technological shifts. Aircraft manufacturers Boeing even predicts it will produce 44,000 planes by 2038 to accommodate the 8 billion passengers flying each year by then. Those planes will look, sound and pollute much like today’s ones.

Aviation is currently forecast to account for almost a quarter of global emissions, and be the UK’s most polluting sector in 2050. And if the government’s recent bail-out of failing airline Flybe is anything to go by, aviation will continue to be let off the hook.

Carbon offsets and “greener” tweaks might only help to further rationalise the status quo, and prevent tougher policies from coming into play – such as taxing frequent flyers, or stopping airport expansions. But as climate-related natural disasters become more common, radically changing our attitude to flying will soon be unavoidable.

https://theconversation.com/people-hate-flight-shame-but-not-enough-to-quit-flying-130614

.

.

Posted: Tuesday, February 18th, 2020. Filed in Climate Change News, General News, Recent News.