A United Nations report raised the threat of climate change to a whole new level on Monday, warning of sweeping consequences to life and livelihood.

The report from the UN’s intergovernmental panel on climate change concluded that climate change was already having effects in real time – melting sea ice and thawing permafrost in the Arctic, killing off coral reefs in the oceans, and leading to heat waves, heavy rains and mega-disasters.

And the worst was yet to come. Climate change posed a threat to global food stocks, and to human security, the blockbuster report said.

“Nobody on this planet is going to be untouched by the impacts of climate change,” said Rajendra Pachauri, chair of the IPCC.

Monday’s report was the most sobering so far from the UN climate panel and, scientists said, the most definitive. The report – a three year joint effort by more than 300 scientists – grew to 2,600 pages and 32 volumes.

The volume of scientific literature on the effects of climate change has doubled since the last report, and the findings make an increasingly detailed picture of how climate change – in tandem with existing fault lines such as poverty and inequality – poses a much more direct threat to life and livelihood.

This was reflected in the language. The summary mentioned the word “risk” more than 230 times, compared to just over 40 mentions seven years ago, according to a count by the Red Cross.

At the forefront of those risks was the potential for humanitarian crisis. The report catalogued some of the disasters that have been visited around the planet since 2000: killer heat waves in Europe, wildfires in Australia, and deadly floods in Pakistan.

“We are now in an era where climate change isn’t some kind of future hypothetical,” said Chris Field, one of the two main authors of the report.

Those extreme weather events would take a disproportionate toll on poor, weak and elderly people. The scientists said governments did not have systems in place to protect those populations. “This would really be a severe challenge for some of the poorest communities and poorest countries in the world,” said Maggie Opondo, a geographer from the University of Nairobi and one of the authors.

The warning signs about climate change and extreme weather events have been accumulating over time. But this report struck out on relatively new ground by drawing a clear line connecting climate change to food scarcity, and conflict.

The report said climate change had already cut into the global food supply. Global crop yields were beginning to decline – especially for wheat – raising doubts as to whether production could keep up with population growth.

“It has now become evident in some parts of the world that the green revolution has reached a plateau,” Pachauri said. [He said “We’re facing the spectre of reduced yields in some of the key crops that feed humanity,” panel chairman Rajendra Pachauri ]

The future looks even more grim. Under some scenarios, climate change could lead to dramatic drops in global wheat production as well as reductions in maize.

“Climate change is acting as a brake. We need yields to grow to meet growing demand, but already climate change is slowing those yields,” said Michael Oppenheimer, a Princeton professor and an author of the report.

Other food sources are also under threat. Fish catches in some areas of the tropics are projected to fall by between 40% and 60%, according to the report.

The report also connected climate change to rising food prices and political instability, for instance the riots in Asia and Africa after food price shocks in 2008.

“The impacts are already evident in many places in the world. It is not something that is [only] going to happen in the future,” said David Lobell, a professor at Stanford University’s centre for food security, who devised the models.

“Almost everywhere you see the warming effects have a negative effect on wheat and there is a similar story for corn as well. These are not yet enormous effects but they show clearly that the trends are big enough to be important,” Lobell said.

The report acknowledged that there were a few isolated areas where a longer growing season had been good for farming. But it played down the idea that there may be advantages to climate change as far as food production is concerned.

Overall, the report said, “Negative impacts of climate change on crop yields have been more common than positive impacts.” Scientists and campaigners pointed to the finding as a defining feature of the report.

The report also warned for the first time that climate change, combined with poverty and economic shocks, could lead to war and drive people to leave their homes.

With the catalogue of risks, the scientists said they hoped to persuade governments and the public that it was past time to cut greenhouse gas emissions and to plan for sea walls and other infrastructure that offer some protection for climate change.

“The one message that comes out of this is the world has to adapt and the world has to mitigate,” said Pachauri.

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/mar/31/climate-change-threat-food-security-humankind

.

.

.

Climate change ‘already affecting food supply’ – UN

- Suzanne Goldenberg in Yokohama (Guardian)

- 31 March 2014

IPCC report, Chapter 7 Food Security and the Food Production System

Climate change has already cut into the global food supply and is fuelling wars and natural disasters, but governments are unprepared to protect those most at risk, according to a report from the UN’s climate science panel.

The report is the first update in seven years from the UN’s international panel of experts, which is charged with producing the definitive account of climate change.

In that time, climate change has ceased to be a distant threat and made an impact much closer to home, the report’s authors say. “It’s about people now,” said Virginia Burkett, the chief scientist for global change at the US geological survey and one of the report’s authors. “It’s more relevant to the man on the street. It’s more relevant to communities because the impacts are directly affecting people – not just butterflies and sea ice.”

The scientists of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found evidence of climate change far beyond thawing Arctic permafrost and crumbling coral reefs – “on all continents and across the oceans“.

But it was the finding that climate change could threaten global food security that caught the attention of government officials from 115 countries who reviewed the report. “All aspects of food security are potentially affected by climate change,” the report said.

The scientists said there was enough evidence to say for certain that climate change is affecting food production on land and sea.

The rate of increase in crop yields is slowing – especially in wheat – raising doubts as to whether food production will keep up with the demand of a growing population. Changes in temperature and rainfall patterns could lead to food price rises of between 3% and 84% by 2050.

“Climate change is acting as a brake. We need yields to grow to meet growing demand, but already climate change is slowing those yields,” said Michael Oppenheimer, a Princeton professor and an author of the report.

Other food sources are also under threat. Fish catches in some areas of the tropics are projected to fall by between 40% and 60%, according to the report.

The report also connected climate change to rising food prices and political instability, for instance the riots in Asia and Africa after food price shocks in 2008.

“The impacts are already evident in many places in the world. It is not something that is [only] going to happen in the future,” said David Lobell, a professor at Stanford University’s centre for food security, who devised the models.

“Almost everywhere you see the warming effects have a negative affect on wheat and there is a similar story for corn as well. These are not yet enormous effects but they show clearly that the trends are big enough to be important,” Lobell said.

Wheat is the first big staple crop to be affected by climate change, because it is sensitive to heat and is grown around the world, from Pakistan to Russia to Canada. Projections suggest that wheat yields could drop 2% a decade.

The report explored a range of scenarios involving a temperature rise of two degrees or more that saw dramatic declines in production in the coming decades. Declines in crop yields will register first in drier and warmer parts of the world but as temperatures rise two, three or four degrees, they will affect everyone.

In the more extreme scenarios, heat and water stress could reduce yields by 25% between 2030 and 2049.

The report acknowledged that there were a few isolated areas where a longer growing season had been good for farming. But it played down the idea that there may be advantages to climate change as far as food production is concerned.

Overall, the report said, “Negative impacts of climate change on crop yields have been more common than positive impacts.” Scientists and campaigners pointed to the finding as a defining feature of the report.

The scientists also detected climate having an effect on heatwaves, droughts and flooding across the globe, and warned that those events would take a disproportionate toll on poor, weak and elderly people. The scientists said governments did not have systems in place to protect those populations. Warming of more than two degrees would increase the risks of “severe, pervasive and irreversible” consequences, the report said.

The report also warned for the first time that climate change, combined with poverty and economic shocks, could lead to war and drive people to leave their homes. “Climate change can indirectly increase risks of violent conflicts,” the report said. It also warned that hundreds of millions of people in south Asia and south-east Asia will be affected by coastal flooding and land loss by 2100.

“The main way that most people will experience climate change is through the impact on food: the food they eat, the price they pay for it, and the availability and choice that they have,” said Tim Gore, head of food policy and climate change for Oxfam.

Friends of the Earth’s executive director, Andy Atkins, said: “We can’t continue to ignore the stark warnings of the catastrophic consequences of climate change on the lives and livelihoods of people across the planet.

“Giant strides are urgently needed to tackle the challenges we face, but all we get is tiny steps, excuses and delays from most of the politicians that are supposed to represent our interests.

“Governments across the world must stand up to the oil, gas and coal industries, and take their foot of the fossil fuel accelerator that’s speeding us towards a climate disaster.”

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/mar/31/climate-change-food-supply-un

.

This IPCC report on food also says, of increasing growing of biofuels:

Water for biofuels, for example, under the IEA Alternative Policy Scenario, which has biofuels production increasing to 71 EJ in 2030, has been reported by Gerbens-Leenes et al. (2012) to drive global consumptive irrigation water use from 0.5% of global

renewable water resources in 2005 to 5.5% in 2030, resulting in increased pressure on freshwater resources, with potential negative impacts on freshwater ecosystems. (Page 44)

and

“Water abstraction for energy, food or biofuel production or carbon sequestration can also

compete with minimal environmental flows needed to maintain riverine habitats and wetlands, implying a potential conflict between economic and other valuations and uses of water.” (Page 44)

.

.

Climate change: the poor will suffer most

- Suzanne Goldenberg in Yokohama (Guardian)

Pensioners left on their own during a heatwave in industrialised countries. Single mothers in rural areas. Workers who spend most of their days outdoors. Slum dwellers in the megacities of the developing world.

These are some of the vulnerable groups who will feel the brunt ofclimate change as its effects become more pronounced in the coming decades, according to a game-changing report from the UN’s climate panel released on Monday. Climate change is occurring on all continents and in the oceans, the authors say, driving heatwaves and other weather-related disasters.

And the changes to the Earth’s climate are fuelling violent conflicts. The UN for the first time in this report has designated climate change a threat to human security.

The overriding lesson of this report, the scientists said, was that unless governments acted now to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and adopt measures to protect their people, nobody would be immune to climate change.

“There isn’t a single region that thinks we can avoid all the impacts of even 2 degrees of warming by adaptation – let alone 4 degrees,” said Dr Rachel Warren of the Tyndall centre for climate change research at the University of East Anglia.

“I think you can say that in order to keep global temperature rises at 2 degrees we need to reduce emissions greatly and rapidly, but even at 2 degrees there are still impacts that we can’t adapt to.”

“We live in an era of manmade climate change,” said Dr Vicente Barros, who chaired the report. “In many cases, we are not prepared for the climate-related risks that we already face. Investments in better preparation can pay dividends both for the present and for the future.”

But those who did the least to cause climate change would be the first in the line of fire: the poor and the weak, and communities that were subjected to discrimination, the report found.

Scientists went to great lengths in the report to single out people and communities who would be most at risk of climate change, with detailed descriptions of locations and demographics.

“People who are socially, economically, culturally, politically, institutionally or otherwise marginalised are especially vulnerable to climate change,” it said.

One impact is through the reduction in crop yields, which leads to higher prices. “The story is that crop yields have detectably changed. As time goes on the poor countries that are in the warmer and drier parts of the planet will feel the crop yield decreases early,” said Michael Oppenheimer, professor of geosciences and international affairs at Princeton University. “When you get above two degrees and into the three- and four-degree range, adaptation becomes less effective and even some of the wealthy countries that have advanced agriculture start suffering.”

“People who were already disadvantaged, more of them are going to be suffering from malnutrition,” he added.

In a further cruel twist, the report said climate change would also make it harder for developing countries to climb out of poverty, and would create “poverty pockets” in rich and poor countries.

It already has. Maarten van Aalst, director of the Red Cross climate centre and an author of the report, said the agency was already seeing evidence that the poor were being hit hardest in weather-related disasters.

“It’s the poor suffering more during disasters, and of course the same hazard causes a much bigger disaster in poorer countries, making it even poorer,” he said.

There are already more weather-related mega-disasters such as heatwaves and storm surges occurring under climate change.

And the number of natural disasters between 2000 and 2009 was around three times higher than in the 1980s, Van Aalst said. “The growth is almost entirely due to ‘climate-related’ events,” he said.

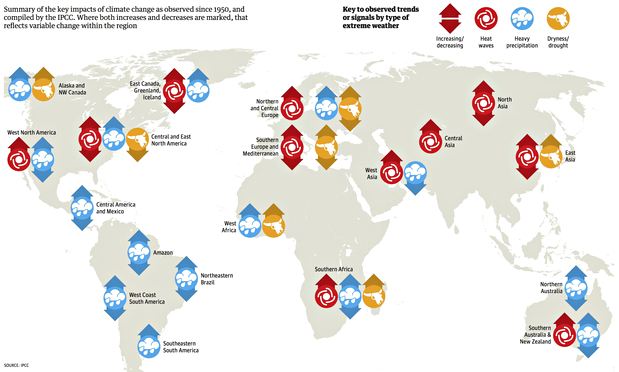

Graphic: guardian.co.ukOther threats are looming because of climate change. The Pentagon and the CIA have released a number of threat assessments in recent years identifying climate change as a threat to military installations, and as a potential driver of conflict – a “threat multiplier“.

Graphic: guardian.co.ukOther threats are looming because of climate change. The Pentagon and the CIA have released a number of threat assessments in recent years identifying climate change as a threat to military installations, and as a potential driver of conflict – a “threat multiplier“.

The UN agrees in this report, saying climate change could lead to war and increased migration.

“Climate change can indirectly increase risks of violent conflicts in the form of civil war and inter-group violence,” the report said.

The authors, however, were cautious about sending the message that climate change causes war per se.

“Climate change, on its own, does not start wars,” said Neil Adger, a professor of geography at Exeter University, and one of the authors of the report. “But it does have a hand in producing situations that lead to conflict.

“The things that drive conflict are sensitive to climate, particularly poverty and economic shocks,” Adger said. “If there is a decrease in food supply or lots of people are pushed into poverty … it creates the environment where you are susceptible to conflict,” he said.

The conflicts are also on a different scale: food riots and unrest triggered by spiralling prices; clashes between farmers and herders of livestock over land and water; competing demands on water for irrigation or for cities.

“It will be within communities or between farmers and it might not necessarily be violent,” Adger said. “It’s more likely to be more local and more site-specific.”

And it could set back efforts to deal with climate change. “Conflict itself actually reduces the ability of places to react to climate change,” Adger added. “The impact of conflict in destabilising regions, wiping out infrastructure, not allowing the state to fulfil its social contract to protect its own people … conflict itself is making people more vulnerable to climate change.”

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/mar/31/climate-change-poor-suffer-most-un-report

.

.