When the latest international Climate Conference wrapped up in Lima, Peru, last month, delegates boarded their flights home without much official discussion of how the planes that shuttled them to the meeting had altered the climate.

Aircraft currently contribute about 2.5 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions. That might not seem like much, but if the aviation industry were a country, it would be one of the world’s top 10 emitters of CO2. And its emissions are projected to grow between two and four times by 2050 without policy interventions.

Left unchecked, aviation emissions could help push global warming over the 2 degrees celsius line. But cutting aviation’s impact poses a daunting challenge.

“Aviation is a global industry. People want global solutions,” said Daniel Rutherford, an environmental engineer at the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT), [author of the article above] an independent nonprofit.

Planes often take off in one country and land in another, making country-by-country regulations impractical. For this reason, the task of addressing aviation’s climate consequences has fallen to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), the United Nations agency in charge of negotiating aviation agreements.

Planes don’t just release carbon dioxide, they also emit nitrogen oxides, sulphur oxides and black carbon, as well as water vapor that can form heat-trapping clouds, said Rutherford, who serves as a technical observer to ICAO’s working groups on climate issues. These emissions take place in the upper troposphere, where their effects are magnified. When this so-called radiative forcing effect is taken into account, aviation emissions produce about 2.7 times the warming effects of CO2 alone, according to estimates by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

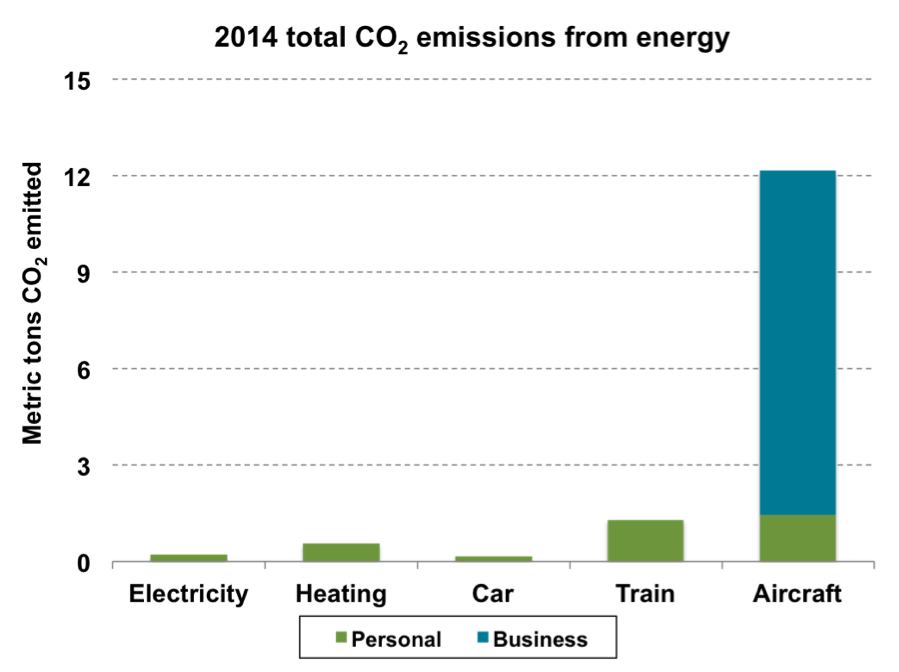

Atmosfair, a German organization that sells “offsets” for people looking to compensate for the flights they take, offers a calculator that takes radiative forcing into account. Its calculations show that a roundtrip flight from, say, Denver to New York produces the equivalent of nearly a year’s worth of emissions from a car, and more than the annual emissions of an average person living in India.

[ The distance between Denver and New York is about 1625 miles (about 2615 km) – which is around the same distance as London to Athens (1484 miles). ]

Basic physics means there’s no way around expending fuel to get a plane in the air. “Aircraft are heavy, so it takes a lot of energy to get them off the ground,” said Alice Bows-Larkin, an atmospheric scientist at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at the University of Manchester.

New aircraft designs can help, but even when new technologies come along, they may take years to reach critical mass in the fleet, because airplanes can last 30 years or more. (And aircraft retired from U.S. fleets often remain in the air when they’re acquired by airlines elsewhere.)

Fuel represents airlines’ No. 1 cost, so they’re highly motivated to optimize fuel efficiency, said Nancy Young, vice president for environment at Airlines for America, an industry trade group. American carriers have already posted impressive efficiency gains of 120 percent since 1978, and that means there isn’t much low-hanging fruit left.

Undaunted, ICAO has pledged to increase fleet fuel efficiency by 1.5 percent per year up to 2020, and it aims for “carbon-neutral growth” after that, with the ultimate goal of reducing CO2 emissions by 50 percent compared to 2005 levels by 2050. The plan depends on improvements in three areas — fuels, aircraft technology and operations — as well as the introduction of so called “market-based mechanisms,” such as carbon offsets.

On the fuels front, work is underway to develop jet fuel from alternative sources such as algae, switch grass and camelina, but it’s uncertain whether these fuels can be created at a rate that meets demand. In 2011, Lufthansa used biofuel on more than 1,100 short-haul flights, but it halted the program after failing to find a reliable source of the fuel. Still, other efforts are underway. United Airlines will start using biofuel on flights out of Los Angeles beginning in the first quarter of 2015 and Southwest also just inked a deal to purchase an alternative fuel made from organic waste.

Meanwhile, incremental changes to aircraft, such as winglets (wing tips that point upward, to reduce drag) and revamped jet engines, are expected to improve fuel efficiency by about 15 to 25 percent by 2020, said Rutherford, the ICCT engineer. [Over about 10 + years or so – ie. a bit over 1.5% perhaps].

Added together with other improvements and more radical aircraft designs, such as a blended wing design that integrates the aircraft body into the wing, these new technologies could eventually triple efficiency, he said.

Operations also offer the potential for gains. The FAA’s NextGen navigation system aims to improve traffic flow through airspace and airports by ensuring that planes are routed via the most efficient path, and by switching over to satellite, rather than ground-based radar navigation systems. One NextGen initiative, the Seattle Greener Skies project, is expected to cut carbon emissions equivalent to taking 4,100 cars off the road.

Despite these promising developments, the numbers show that ICAO’s emissions targets will be impossible to achieve. ICAO readily acknowledges this, which is why it has agreed to develop a global market-based measure to address emissions, a plan its members agreed to at their 2013 assembly in Montreal. The plan would allow the aviation sector to buy the right to emit greenhouse gases from other industries, in the form of carbon credits.1Such a plan is absolutely necessary if ICAO is to meet its targets, because nothing else can bring emissions into line.

The charts below (taken from a report by researchers at Manchester Metropolitan University) show the emission reductions projected for various combinations of approaches: technology and operations, biofuel and emissions trading (MBM-ETS, for market-based measures and emissions trading systems in the chart). These approaches are compared to three objectives (based on the ICAO plan) — a 2 percent per year gain in efficiency, carbon-neutral growth from 2020 and a reduction to 2005 emission levels. Even added together, none of these approaches comes close to meeting the latter two goals.

The European Union’s Emissions Trading System (ETS) was set to include aviation emissions, which would have forced U.S. airlines that take off and land in the EU to participate. But after Congress and President Obama blocked American carriers from complying with the rules, the EU backed off.

Despite such political resistance, the U.S. may soon enact new limits on aviation emissions. The Environmental Protection Agency is working on rules to address carbon dioxide emissions from aircraft after environmental groups forced the agency’s hand by suing to regulate aviation emissions as pollutants. The EPA is currently scheduled to propose its findings in late April this year and then make final determinations sometime in the spring of 2016. The U.S. is responsible for about a third of global aviation emissions, so action by the EPA would be “very significant,” Rutherford said, though how ambitious the EPA’s standards might be remains an open question.

Young’s group expects that the EPA standards will align with the CO2 standards ICAO is currently formulating, due for release in 2016. “There’s no one silver bullet — it’s silver buckshot,” she said. “You have to shoot a lot of these pellets.” She said reducing emissions can be done without making flights prohibitively expensive.

One option that’s not part of ICAO’s plan is reducing demand for flights. Doing so might sound radical, but a sober look at the numbers shows that it may be necessary.

Alice Bows-Larkin recently published an analysis concluding that the aviation industry is placing too much hope on emissions trading to help it attain CO2 reductions that would keep it in line with the 2 degrees goal for limiting global warming. Achieving this goal, she concluded, will require flying less.

“Flight is the most carbon-intensive activity that we can do,” said Bows-Larkin, who hasn’t flown since 2005.

Carbon dioxide released into the atmosphere today can stick around for a hundred years, and it can’t easily be recaptured. The urgency of the problem requires a solution sooner rather than later, she said. “Time is massively against us.”

http://fivethirtyeight.com/features/every-time-you-fly-you-trash-the-planet-and-theres-no-easy-fix/